464

Ibid. For a more detailed characterization of natsiokratiia, see Bruder, Den ukrainischen Staat erkampfen oder sterben, 34–35.

TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 7, ll. 2, 7.

Ibid., l. 7.

The term "integral nationalism" became popular among historians of nationalism in the 1940s. Integral nationalism has been associated with the OUN and the Ukrainian nationalist movement since studies such as John Armstrong's Ukrainian Nationalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1955), 19–21. To some extent, this is a problematic connection. The term "integral nationalism" was invented by the protofascist French monarchist Charles Maurras. Like Maurras, the OUN claimed that the nation is a "prior condition of every social and individual good" but the OUN did not claim, for example, that the "traditional hereditary monarchy" is a necessary condition for a state, as Maurras did. For this and several other reasons, the Ukrainian nationalist movement and in particular the OUN in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s can by no means be reduced to integral nationalism. Nor did contemporary ideologists of Ukrainian nationalism, like Dmytro Dontsov, who inspired the OUN in the 1920s and 1930s, use this term. Dontsov frequently characterized Ukrainian nationalism as being fascist and nationalistic, claiming that it belonged to the family of European fascist movements. From the contemporary point of view, Armstrong's Ukrainian Nationalism is a problematic study. It is partially based on interviews with OUN activists and UPA veterans and misses many important archival documents that were not accessible during the Cold War. Due to his method of investigation, Armstrong misses such crucial events as pogroms against the Jews in western Ukraine in the summer of 1941 and the ethnic cleansing of the Polish population by the UPA in Volhynia and Galicia in 1943-44. On Charles Maurras and integral nationalism, see Steve Bastow, "Integral Nationalism," in World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia, ed. Cyprian P. Blamires (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC–CLIO, 2006), 1:338. On Dontsov, see Tomasz Stryjek, Ukrainska idea narodowa okresu miedzywojennego: Analizy wybranych koncepcji (Wrodaw: FUNNA, 2000), 118-19, 132, 139-40, 143-51; Taras Kurylo and John-Paul Himka, "Iak OUN stavylasia do ievreiv: Formulovannia pozytsii na tli katastrofy," Ukraina moderna 13, 2 (2008): 264; and Motyl, The Turn to the Right, 68, 71–85.

Motyl, The Turn to the Right, 163-69. Heorhii Kas" ianov, in an article about the ideology of the OUN ("Ideolohiia OUN: Istoryko-retrospektyvnyi analiz," Ukrains "kyi istorychnyi zhurnal 1 [2004]: 38–41), recently came to a similar conclusion. Kas" ianov's study emphasized the uniqueness of the OUN and underestimated ideological transfer from outside, quoting dubious semi-scholars from the OUN like Petro Mirchuk. The study lacks a sufficiently analytical approach, although it does provide a few useful interpretations of Ukrainian ideology.

Daniel Ursprung, "Faschismus in Ostmittel- und Siidosteuropa: Theorien, Ansatze, Fragestellungen," in Der Einfluss yon Faschismus und Nationalsozialismus auf Minderheiten in Ostmittel-und Siidosteuropa, ed. Mariana Hausleimer and Harald Roth (Munich: IKGS-Verlag, 2006), 22. For the peculiarities of East European fascism, see also Stephen FischerGalati, "Introduction," in Who Were the Fascists? Social Roots of European Fascism, ed. Stein Ugelvik Larsen, Bernt Hagtvet, and Jan Petter Myklebust (Bergen: Universitetsforlaget, 1980), 351-53.

For the incorporation of the League of Ukrainian Fascists into the OUN in 1929, see Frank Golczewski, Deutsche und Ukrainer 1914–1939 (Padeborn: Schoningh, 2010), 550; Oleksandr Panchenko, Mykola Lebed" (zhyttia, dial'nist; derzhavno-pravovi pohliady) (Kobeliaky: Kobeliaky, 2001), 15.

Excellent discussions of the theory of fascism, in addition to characterizations of fascism and fascist movements, can be found in Michael Mann, Fascists (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 1-23; Roger Eatwell, Fascism: A History (London: Chatto and Windus, 1995), 3-12; Roger Griffin, The Nature of Fascism (London: Pinter, 1991), 1-19; Jerzy W. Borejsza, Schulen des Hasses: Faschistische Systeme in Europa (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer TB, 1999), 54–56; Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism, 1914–1945 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995), 3-19, 26–52; and Wolfgang Wippermann, Faschismus: Eine Weltgeschichte vom 19. Jahrhundert his heute (Darmstadt: Primus, 2009). For the influence of fascism on East Central and Southeastern Europe, see Ursprung, "Faschismus in Ostmittel-und Sudosteuropa," 9-52.

The other Ukrainian term for leader-vozhd'-was reserved for Andrii Mel'nyk after the Second General Congress of the OUN on 27 August 1939. Therefore, the OUN-B, to distinguish its Fuhrerprinzip from that of the OUN-M, called Bandera providnyk. For more on this congress, see Golczewski, Deutsche und Ukrainer 1914–1939, 943-44.

TsDAHO f. 1, op. 23, spr. 926, ll. 199–202, 207.

Ibid., l. 199. This salute later embarrassed the OUN. In postwar publications reprinting the resolutions of the Second General Congress of the OUN-B in April 1941, the resolution about the fascist salute was deleted from the text. Compare, for example, OUN v svitli postanov Velykykh zboriv (s.l.: Zakordonni chastyny Orhanizatsii ukrains'kykh natsionalistiv, 1955), 44–45, with the original publication Postanovy II: Velykoho zboru Orhanizatsii ukrains 'kykh natsionalistiv of 1941 in TsDAHO f. 1, op. 23, spr. 926, 1. 199.

TsDAHO f. 1, op. 23, spr. 926, ll. 190-93.

For a rethinking of these elements of fascism in the OUN, see O. I. Steaniv, "Za pravvl'nvi pidkhid," in Ideia i chyn. no. 2 (1943): 22. For a resolution to collect and remove from circulation documents which discussed the involvement of Ukrainian militia in the pogroms of 1941 and their assistance to the Germans in the shooting of Jews, see Kurylo and Himka, "Iak OUN stawlasia do ievreiv," 260. See also the document itself: TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 43, 1.9 (Nakaz ch. 2/43). On the process of "democratization," see David R. Marples, Heroes and Villains: Creating National History in Contemporary Ukraine (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2007), 194-96.

Grelka, Die ukrainische Nationalbewegung, 269.

On the "Generalplan Ost," see Czeshw Madajczyk, "Vom Generalplan Ost zum Generalumsiedlungsplan," in Der "Generalplan Ost"." Hauptrichtungen der nationalsozialistischen Planungs- und Vernichtungspolitik, ed. Mechtild Rossler and Sabine Schleiermacher (Berlin: Akademie, 1993), vii. For Hitler's attitude toward Eastern Europeans and Ukraine, see Czeshw Madajczyk, Vom Generalplan Ost zum Generalumsiedlungsplan (Munich: Saur, 1994), 23–25; and Henry Picker, Hitler Tischgesprache: Im Fuhrerhauptquartier 1941–1942 (Bonn: Athenaum, 1951), 50–51, 69, 115-16.

Hans Werner Neulen, An deutscher Seite: Internationale Freiwillige yon Wehrmacht und Waffen-SS (Munich: Universitas, 1992), 17.

TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 69, 11. 23–28 (Propahandyvni Vkazivki na peredvoennyi chas, na chas viiny i revoliutsii ta na pochatkovi dhi derzhavnoho budivnytstva).

Ibid., II. 23, 25–28. The OUN-B modified, for example, the hymn of the European prole tariat, "The Internationale," for use in its "national revolution." See ibid., 1.25.

Ibid., 1. 24; ibid., op. 2, spr. 1, l. 80 (Borot'ba i diial'nist" OUN pid chas viiny). In Ukrainian Vbyvaite vorohiv, shcho mizh vamy-zhydiv, i seksotiv. This slogan was developed for factory workers.

Ibid., op. 1, spr. 69, 1.26.

Ibid., 1.43.

Ibid., 1.26.

Ibid., 1.27. For details on how the OUN-B wanted to control the political situation in the Ukrainian state, see ibid.,op.2, spr.1, l1.44–45.

Ibid., op. 2, spr. 1, 11. 15–89.

Ibid.,op.1,spr.15,1.7(Internal telegram of the OUN,31July 1941)

Ibid., op. 2, spr. 1, l. 32.

Ibid., Il. 22, 31–32, 83.

TsDAHO f. 1, op. 23, spr. 926, ll. 188, 193.

TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 2, spr. I, l. 2.

TsDAHO f. 1, op. 23, spr. 926, l. 189; Klymyshyn, V pokhodido voli, 303-4, 311-13.

Armstrong, Ukrainian Nationalism, 77.

Ibid., 79–80.

"Aufzeichnungen des Vortragenden Legationsrats Grosskopf," Akten zur deutschen Auswartigen Politik 1918–1945, Serie D, Band XIII, ed. Walter Bussmann (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1970), 167-68. See also Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde (BA Berlin-Lichterfelde) R. 6 (Reichsministerium fur die Besetzen Ostgebiete)/150, 11. 4–5 (Rucksprache mit Prof. Dr. Koch am 10.7.1941); and Kost' Pankivs'kyi, Vid derzhavy do komitetu (New York Toronto: Zhyttia i mysli,1957),30–32.

Iaroslav Stets'ko dubbed the arrest of Stepan Bandera a "confiscation" (TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 6, l.2).

Ibid., spr. 5, l.3 (from the proclamation act signed by Iaroslav Stets'ko).

Ibid., 1.3.

Ibid., spr. 4, l. 6 (Minutes of the proclamation ceremony).

Ibid., spr. 57, l. 17 (Autobiographies of well-known OUN members); Bruder, Den ukrain ischen Staat erkampfen oder sterben, 150.

TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 4, l. 7.

Myroslav Kal'ba, U lavakh druzhynnykiv (Denver: Vydannia Druzhyn ukrains'kykh nat sionalistiv, 1982), 9-10; BA Berlin-Lichterfelde: NS 26 (Hauptarchiv NSDAP)/1198, I. 1 (Information leaflet no. 1, 1 July 1941).

BA Berlin-Lichterfelde: NS 26/1198, ll. 1, 12 (Niederschrift uber die Rucksprache mit den Mitgliedem des ukrainischen Nationalkomitees und Stepan Bandera von 3.7.1941).

Ibid., l. 2.

Ibid., ll. 1–3. For Sheptyts'kyi's pastoral letter, see OUN v svitli postanov Velykykh Zboriv (s.l.: Zakordonni chastyny Orhanizatsii Ukrains'kykh Natsionalistiv, 1955), 58.

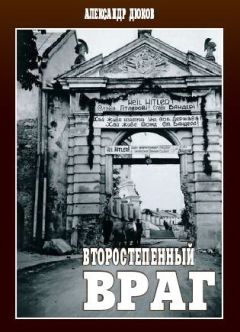

For an OUN-B instruction to erect triumphal arches, see TsDAVOV f. 4620, op. 3, spr. 379, l.34 (Instruktsiia propahandy, ch. 1). For pictures and descriptions of triumphal arches, see V. Cherednychenko, Natsionalizm proty natsii (Kyiv: Politvydav Ukrainy, 1970), 93; Grelka, Die ukrainische Nationalbewegung, 256; Archiwum Wschodnie (AW) II/737, l.25; and the cover of Aleksandr Diukov, Vtorostepennyi vrag: OUN, UPA i reshenie "evreiskogo voprosa" (Moscow: Regnum, 2008).

BA Berlin-Lichterfelde: R 58 (Reichssicherheitshauptamt)/214, Ereignismeldungen UdSSR, Berlin, 17 July 1941, no. 25, l. 202.

TsDAVOV f. 4620, op. 3, spr. 379, l. 34.

TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 15, l. 4 (Zvit pro robotu v spravi orhanizatsii derzhavnoi administratsii na tereni Zakhidnykh oblastei Ukrainy). For a photo of Sheptyts'kyi with a swastika badge on his coat during the revolution, see B. E Sabrin, Alliance for Murder: The Nazi-Ukrainian Nationalist Partnership in Genocide (New York: Sarpedon, 1991), 172.

TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 45, l.3. By claming that he "saw Bandera twice under the gallows unconquerable and loyal to the idea," Klymiv meant the trials against the OUN in 1935-36 in Warsaw and in 1936 in L'viv, at which Bandera was sentenced to death but was said not to have expressed any fear. At the second trial the death penalty was changed to life imprisonment.

The picture of a German officer and two men in plain clothes at the podium is printed in Cherednychenko, Natsionalizm praty natsii, 93. For the date of this event, see TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 15, l. 15.

TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 22, ll. 1–3.

Ibid., op. 3, spr. 7, l. 26.

Ibid., op. 1, spr. 10, l. 4 (A list of deputies of the Ukrainian government abroad).

BA Berlin-Lichterfelde, R 58/214, Ereignismeldungen UdSSR. Berlin, 4 July 1941, no. 12, I. 69. On the Council of Seniors, see also TsDAVOV f. 3833, op. 1, spr. 15, l.3.

On all the projects of the state apparatus drafted by Stepaniak, see Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii (GARF) f. R-9478 (Glavnoe upravlenie po bor'be s banditizmom MVD SSR), op. 1, d. 136, ll. 14–15. On Stepaniak's communist activities in the 1930s, see ibid., l. 10.