Outside she fastened her coat against the rising wind. The top button was missing so she covered her throat with her hand. A bright space opened in her head and memory seeped into it.

Standing on the riverbank in a purple-and-white dress, Sula swinging Chicken Little around and around. His laughter before the hand-slip and the water closing quickly over the place. What had she felt then, watching Sula going around and around and then the little boy swinging out over the water? Sula had cried and cried when she came back from Shadrack’s house. But Nel had remained calm.

“Shouldn’t we tell?”

“Did he see?”

“I don’t know. No.”

“Let’s go. We can’t bring him back.”

What did old Eva mean by you watched? How could she help seeing it? She was right there. But Eva didn’t say see, she said watched. “I did not watch it. I just saw it.” But it was there anyway, as it had always been, the old feeling and the old question. The good feeling she had had when Chicken’s hands slipped. She hadn’t wondered about that in years. “Why didn’t I feel bad when it happened? How come it felt so good to see him fall?”

All these years she had been secretly proud of her calm, controlled behavior when Sula was uncontrollable, her compassion for Sula’s frightened and shamed eyes. Now it seemed that what she had thought was maturity, serenity and compassion was only the tranquillity that follows a joyful stimulation. Just as the water closed peacefully over the turbulence of Chicken Little’s body, so had contentment washed over her enjoyment.

She was walking too fast. Not watching where she placed her feet, she got into the weeds by the side of the road. Running almost, she approached Beechnut Park. Just over there was the colored part of the cemetery. She went in. Sula was buried there along with Plum, Hannah and now Pearl. With the same disregard for name changes by marriage that the black people of Medallion always showed, each flat slab had one word carved on it. Together they read like a chant: PEACE 1895–1921, PEACE 1890–1923, PEACE 1910–1940, PEACE 1892–1959.

They were not dead people. They were words. Not even words. Wishes, longings.

All these years she had been harboring good feelings about Eva; sharing, she believed, her loneliness and unloved state as no one else could or did. She, after all, was the only one who really understood why Eva refused to attend Sula’s funeral. The others thought they knew; thought the grandmother’s reasons were the same as their own—that to pay respect to someone who had caused them so much pain was beneath them. Nel, who did go, believed Eva’s refusal was not due to pride or vengeance but to a plain unwillingness to see the swallowing of her own flesh into the dirt, a determination not to let the eyes see what the heart could not hold.

Now, however, after the way Eva had just treated her, accused her, she wondered if the townspeople hadn’t been right the first time. Eva was mean. Sula had even said so. There was no good reason for her to speak so. Feebleminded or not. Old. Whatever. Eva knew what she was doing. Always had. She had stayed away from Sula’s funeral and accused Nel of drowning Chicken Little for spite. The same spite that galloped all over the Bottom. That made every gesture an offense, every off-center smile a threat, so that even the bubbles of relief that broke in the chest of practically everybody when Sula died did not soften their spite and allow them to go to Mr. Hodges’ funeral parlor or send flowers from the church or bake a yellow cake.

She thought about Nathan opening the bedroom door the day she had visited her, and finding the body. He said he knew she was dead right away not because her eyes were open but because her mouth was. It looked to him like a giant yawn that she never got to finish. He had run across the street to Teapot’s Mamma, who, when she heard the news, said, “Ho!” like the conductor on the train when it was about to take off except louder, and then did a little dance. None of the women left their quilt patches in disarray to run to the house. Nobody left the clothes halfway through the wringer to run to the house. Even the men just said “uhn,” when they heard. The day passed and no one came. The night slipped into another day and the body was still lying in Eva’s bed gazing at the ceiling trying to complete a yawn. It was very strange, this stubbornness about Sula. For even when China, the most rambunctious whore in the town, died (whose black son and white son said, when they heard she was dying, “She ain’t dead yet?”), even then everybody stopped what they were doing and turned out in numbers to put the fallen sister away.

It was Nel who finally called the hospital, then the mortuary, then the police, who were the ones to come. So the white people took over. They came in a police van and carried the body down the steps past the four pear trees and into the van for all the world as with Hannah. When the police asked questions nobody gave them any information. It took them hours to find out the dead woman’s first name. The call was for a Miss Peace at 7 Carpenter’s Road. So they left with that: a body, a name and an address. The white people had to wash her, dress her, prepare her and finally lower her. It was all done elegantly, for it was discovered that she had a substantial death policy. Nel went to the funeral parlor, but was so shocked by the closed coffin she stayed only a few minutes.

The following day Nel walked to the burying and found herself the only black person there, steeling her mind to the roses and pulleys. It was only when she turned to leave that she saw the cluster of black folk at the lip of the cemetery. Not coming in, not dressed for mourning, but there waiting. Not until the white folks left—the gravediggers, Mr. and Mrs. Hodges, and their young son who assisted them—did those black people from up in the Bottom enter with hooded hearts and filed eyes to sing “Shall We Gather at the River” over the curved earth that cut them off from the most magnificent hatred they had ever known. Their question clotted the October air, Shall We Gather at the River? The beautiful, the beautiful river? Perhaps Sula answered them even then, for it began to rain, and the women ran in tiny leaps through the grass for fear their straightened hair would beat them home.

Sadly, heavily, Nel left the colored part of the cemetery. Further along the road Shadrack passed her by. A little shaggier, a little older, still energetically mad, he looked at the woman hurrying along the road with the sunset in her face.

He stopped. Trying to remember where he had seen her before. The effort of recollection was too much for him and he moved on. He had to haul some trash out at Sunnydale and it would be good and dark before he got home. He hadn’t sold fish in a long time now. The river had killed them all. No more silver-gray flashes, no more flat, wide, unhurried look. No more slowing down of gills. No more tremor on the line.

Shadrack and Nel moved in opposite directions, each thinking separate thoughts about the past. The distance between them increased as they both remembered gone things.

Suddenly Nel stopped. Her eye twitched and burned a little.

“Sula?” she whispered, gazing at the tops of trees. “Sula?”

Leaves stirred; mud shifted; there was the smell of overripe green things. A soft ball of fur broke and scattered like dandelion spores in the breeze.

“All that time, all that time, I thought I was missing Jude.” And the loss pressed down on her chest and came up into her throat. “We was girls together,” she said as though explaining something. “O Lord, Sula,” she cried, “girl, girl, girlgirlgirl.”

It was a fine cry—loud and long—but it had no bottom and it had no top, just circles and circles of sorrow.

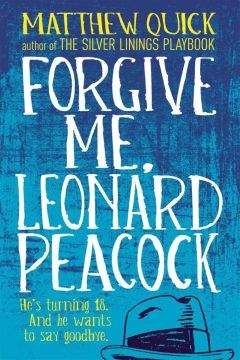

TONI MORRISON

Sula

Toni Morrison is the Robert F. Goheen Professor of Humanities at Princeton University. She has received the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Pulitzer Prize. In 1993 she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. She lives in Rockland County, New York, and Princeton, New Jersey.

ALSO BY TONI MORRISON

FICTION

Love

Paradise

Jazz

Beloved

Tar Baby

Song of Solomon

The Bluest Eye

NONFICTION

The Dancing Mind

Playing in the Dark:

Whiteness and the Literary Imagination

ACCLAIM FOR TONI MORRISON’S

Sula

“Sula is one of the most beautifully written, sustained works of fiction I have read in some time…. [Morrison] is a major talent.”

—Elliot Anderson, Chicago Tribune

“As mournful as a spiritual and as angry as a clenched fist…written in language so pure and resonant that it makes you ache.”

—Playboy

“In the first ranks of our living novelists.”

—St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“Toni Morrison’s gifts are rare: the re-creation of the black experience in America with both artistry and authenticity.”

—Library Journal

“Should be read and passed around by book lovers everywhere.”

—Los Angeles Free Press

FIRST VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL EDITION, JUNE 2004

Copyright © 1973, 2004, and renewed 2002 by Toni Morrison

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in slightly different form in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1974.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage International and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Morrison, Toni.

Sula.

I. Title.

PZ4.M883Su [PS3563.08749]

813'.5'4

73-7278

www.vintagebooks.com

eISBN: 978-0-307-38813-1

v3.0