"I do not see why he could not have been kept with the other prisoners," Osborne said.

"No, of course you do not," Mayhew replied.

"The Tower's main rooms have held two kings of Scotland and a king of France, our own King Henry VI, Thomas More, and our own good queen. What is so special about this one that he deserves more secure premises than those great personages?" Osborne persisted.

"You have only been assigned to this task for two days," Mayhew replied. "When you have been here as long as I, you will understand."

Crossing the room, Mayhew peered through the bars in the door. As his eyes adjusted to the gloom within, he made out the form of the cell's occupant hunched on a rough wooden bench, the hood of his cloak, as always, pulled over his head so his features were hidden. He was allowed no naked flame for illumination, no drink in a bowl or goblet, only in a bottle, and he was never allowed to leave the secure area of the White Tower where he had been imprisoned for twenty years.

"Still nothing to say?" Mayhew murmured, and then laughed at his own joke. He passed the comment every day, in full knowledge that the prisoner had never been known to speak in all his time in the Tower.

Yet on this occasion the light leaking through the grille revealed a subtle shift in the dark shape, as though the prisoner was listening to what Mayhew said, perhaps even considering a response.

Mayhew's deliberations were interrupted by muffled bangs and clatters in the Mint above their heads, the sound of raised voices, and then a low, chilling cry.

"They are in," he said flatly, turning back to the room.

Osborne had pressed himself against one wall like a hunted animal. The four guards looked to Mayhew hesitantly.

"Help your friends," he said. "Do whatever is in your power to protect this place. Lock the door as you leave. I will bolt it."

Once they had gone, he slammed the bolts into place with a flick of his wrist that showed his disdain for their security.

"You know it will do no good," Osborne said. "If they have gained access to the Mint, there is no door that will keep them out."

"What do you suggest? That we beg for mercy, or run screaming, like girls?"

"Pray," Osborne replied, "for that is surely the only thing that can save us. These are not men that we face, not Spaniards, or French, not the Catholic traitors from within our own realm. These are the Devil's own agents, and they come for our immortal souls."

Mayhew snorted. "Forget God, Osborne. If He even exists, He has scant regard for this vale of misery."

Osborne recoiled as if he had been struck. "You do not believe in the Lord?"

"If you want atheism, talk to Marlowe. He makes clear his views with every action he takes. But I learn from the evidence of my own eyes, Osborne. We face a threat that stands to wipe us away as though we had never been, and if there is to be salvation, it will not come from above. It will be achieved by our own hand."

"Then help me barricade the door," Osborne pleaded.

With a sigh and a shrug, Mayhew set his weight against the great oak table, and with Osborne puffing and blowing beside him, they pushed it solidly against the door.

When they stood back, Mayhew paused as the faint strains of the haunting pipe music reached him again, plucking at his emotions, turning him in an instant from despair to such ecstasy that he wanted to dance with wild abandon. "That music," he said, closing his eyes in awe.

"I hear no music!" Osborne shouted. "You are imagining it."

"It sounds," Mayhew said with a faint smile, "like the end of all things." He turned back to the cell door where the prisoner now waited, the torchlight catching a metallic glint beneath his hood.

"Damn your eyes!" Osborne raged. "Return to your bench! They shall not free you!"

Unmoving, the prisoner watched them through the grille. Mayhew did not sense any triumphalism in his body language, no sign that he was assured of his freedom, merely a faint curiosity at the change to the pattern that had dominated his life for so many years.

"Sit down!" Osborne bellowed.

"Leave him," Mayhew responded as calmly as he could manage. "We have a more pressing matter."

Above their heads, the distant clamour of battle was punctuated by a muffled boom that shook the heavy door and brought a shower of dust from the cracks in the stone. Silence followed, accompanied by the cloying scent of honeysuckle growing stronger by the moment.

Drawing their swords, Mayhew and Osborne focused their attention on the door.

A random scream, becoming a sound like the wind through the trees on a lonely moor. More noises, fragments of events that painted no comprehensive picture.

Breath tight in their chests, knuckles aching from gripping their swords, Mayhew and Osborne waited.

Something bouncing down the stone steps, coming to rest against the door with a thud.

A soft tread, then gone like a whisper in the night, followed by a long silence that felt like it would never end.

Finally the unbearable quiet was broken by a rough grating as the top bolt drew back of its own accord. His eyes frozen wide, Osborne watched its inexorable progress.

As soon as the bolt had clicked open, the one at the foot of the door followed, and when that had been drawn the great tumblers of the iron lock turned until they fell into place with a shattering clack.

"I ... I think I can hear the music now, Mayhew, and there are voices in it," Osborne said. He began to recite the Lord's Prayer quietly.

The door creaked open a notch and then stopped. Light flickered through the gap, not torchlight or candlelight, but with some troubling quality that Mayhew could not identify, but which reminded him of moonlight on the Downs. The music was louder now, and he too could hear the voices.

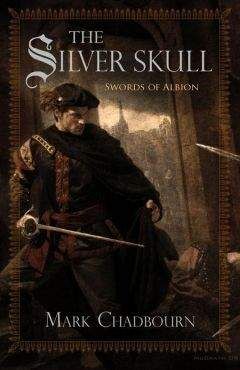

A sound at his back disrupted his thoughts. The prisoner's hands were on the bars of the grille and he had removed his hood for the first time that Mayhew could recall. In the ethereal light, there was an echo of the moon within the cell. The prisoner's head was encompassed by a silver skull of the finest workmanship, gleaming so brightly Mayhew could barely look at it. Etched on it with almost invisible black filigree were ritual marks and symbols. Through the silver orbits, the prisoner's eyes hung heavily upon Mayhew, steady and unblinking, the whites marred by a tracing of burst capillaries.

The door opened.

CHAPTER 1

ven four hours of soft skin and full lips could not take away her face. Empty wine bottles rattling on the bare boards did not drown out her voice, nor did the creak of the bed and the gasps of pleasure. She was with him always.

"They say you single-handedly defeated ten of Spain's finest swordsmen on board a sinking ship in the middle of a storm," the redheaded woman breathed in his ear as she ran her hand gently along his naked thigh.

"True."

"And you broke into the Doge's palace in disguise and romanced the most beautiful woman in all of Venice," the blonde woman whispered into his other ear, stroking his lower belly.

"Yes, all true."

"And you wrestled a bear and killed it with your bare hands," the redhead added.

He paused thoughtfully, then replied, "Actually, that one is not true, but I think I will appropriate it nonetheless."

The women both laughed. He didn't know their names, didn't really care. They would be amply rewarded, and have tales to tell of their night with the great Will Swyfte, and he would have passed a few hours in the kind of abandon that always promised more than it actually delivered.

"Your hair is so black," the blonde one said, twirling a finger in his curls.

"Yes, like my heart."

They both laughed at that, though he wasn't particularly joking. Nathaniel would have laughed too, although with more of a sardonic edge.

The redhead reached out a lazy hand to examine his clothes hanging over the back of the chair. "You must cut a dashing figure at court, with these finest and most expensive fashions." Reaching a long leg from the bed, she traced her toes across the shiny surface of his boots.

"I heard you were a poet." The blonde rubbed her groin gently against his hip. "Will you compose a sonnet to us?"

"I was a poet. And a scholar. But that part of my life is far behind me."

"You have exchanged it for a life of adventure," she said, impressed. "A fair exchange, for it has brought you riches and fame."

Will did not respond.

The blonde examined his bare torso, which bore the tales of the last few years in each pink slash of a rapier scar or ragged weal of torture, stories that had filtered into the consciousness of every inhabitant of the land, from Carlisle to Kent to Cornwall.

As she swung her leg over him to begin another bout of lovemaking, they were interrupted by an insistent knocking at the door.

"Go away," Will shouted.

The knocking continued. "I know you are deep in doxie and sack, Master Swyfte," came a curt, familiar voice, "but duty calls."

"Nat. Go away."

The door swung open to reveal Nathaniel Colt, shorter than Will and slim, but with eyes that revealed a quick wit. He studiedly ignored the naked, rounded bodies and focused his attention directly on Will.

"A fine place to find a hero of the realm," he said with sarcasm. "A tawdry room atop a stew, stinking of coitus and spilled wine."

"In these harsh times, every man deserves his pleasures, Nat."

"This is England's greatest spy," the redhead challenged. "He has earned his comforts."

"Yes, England's greatest spy," Nathaniel replied acidly. "Though I remain unconvinced of the value of a spy whose name and face are recognised by all and sundry."

"England needs its heroes, Nat. Do not deny the people the chance to celebrate the successes of God's own nation." He eased the women off the bed with gentle hands. "We will continue our relaxation at another time," he said warmly, "for I fear my friend is determined to enforce chastity."

His eyes communicated more than his words. The women responded with coquettish giggles as they scooped up their dresses to cover them as they skipped out of the room.

Kicking the door shut after them, Nathaniel said, "You will catch the pox if you continue these sinful ways with the Winchester Geese."

"The pox is not God's judgment, or all the aristocracy of England would be rotting in their breeches as they dance at court."

"And 'twould be best if you did not let any but me hear your views on our betters."

"Besides," Will continued, "Liz Longshanks' is a fine establishment. Does it not bear the mark of the Cardinal's Hat? Is this land on which this stew rests not in the blessed ownership of the bishop of Winchester? Everything has two faces, Nat, neither good nor bad, just there. That is the way of the world, and if there is a Lord, it is His way."

Ignoring Nathaniel's snort, Will stretched the kinks from his limbs and lazily eased out of the bed to dress, absently kicking the empty bottles against the chamber pot. "And," he added, "I am in good company. That master of theatre, Philip Henslowe, and his son-in-law Edward Alleyn are entertaining Liz's girls in the room below."

"Alleyn the actor?"

"Whoring and acting go together by tradition, as does every profession that entails holding one face to the world and another in the privacy of your room. When you cannot be yourself, it creates certain tensions that must be released."

"You will be releasing more tensions if you do not hurry. Your Lord Walsingham is on his way to Bankside, and if he finds his favoured tool deep in whores, or in his cups, he will be less than pleased." Nathaniel threw Will his shirt to end his frustrated searching.

"What trouble now, then? More Spanish spies plotting against our queen? You know they fall over their own swords."

"I am pleased to hear you take the threats against us so lightly. England is on the brink of war with Spain, the nation is torn by fears of the enemy landing on our shores at every moment, we lack adequate defences, our navy is in disarray, we are short of gunpowder, and the great Catholic powers of Europe are all eager to see us crushed and returned to the old faith, but the great Will Swyfte thinks it is just a trifling. I can rest easily now."

"One day you will cut yourself with that tongue, Nat."

"There is some trouble at the White Tower, though I am too lowly a worm to be given any important details. No, I am only capable of dragging my master out of brothels and hostelries and keeping him one step out of the Clink," he added tartly.

"You are of great value to me, as well you know." Finishing his dressing, Will ran a hand through his hair thoughtfully. "The Tower, you say?"

"An attempt to steal our gold, perhaps. Or the Crown jewels. The Spanish always look for interesting ways to undermine this nation."

"I cannot imagine Lord Walsingham venturing into Bankside for bullion or jewels." He ensured Nathaniel didn't see his mounting sense of unease. "Let us to the Palace of Whitehall before the principal secretary sullies his boots in Bankside's filth."

A commotion outside drew Nathaniel to the small window, where he saw a sleek black carriage with a dark red awning and the gold brocade and ostrich feathers that signified it had been dispatched from the palace. The chestnut horse stamped its hooves and snorted as a crowd of drunken apprentices tumbled out of the Sugar Loaf across the street to surround the carriage.

"I fear it is too late for that," Nathaniel said.

Four accompanying guards used their mounts to drive the crowd back, amid loud curses and threats but none of the violence that troubled the constables and beadles on a Saturday night. Two of the guards barged into the brothel, raising angry cries from Liz Longshanks and the girls waiting in the downstairs parlour, and soon the clatter of their boots rose up the wooden stairs.

"Let us meet them halfway," Will said.

"If I were you, I would wonder how our Lord Walsingham knows exactly which stew is your chosen hideaway this evening."

"Lord Walsingham commands the greatest spy network in the world. Do you think he would not use a little of that power to keep track of his own?"

"But you are in his employ."

"As the queen's godson likes to say, `treason begets spies and spies treason.' In this business, as perhaps in life itself, it is best not to trust anyone. There is always another face behind the one we see."

"What a sad life you lead."

"It is the life I have. No point bemoaning." Will's broad smile gave away nothing of his true thoughts.

The guards escorted him out into the rutted street, where a light frost now glistened across the mud. The smell of ale and woodsmoke hung heavily between the inns and stews that dominated Bankside, and the night was filled with the usual cacophony of cries, angry shouts, the sound of numerous simultaneous fights, the clatter of cudgels, cheers and roars from the bulland bear-baiting arenas, music flooding from open doors, and drunken voices singing clashing songs. Every conversation was conducted at a shout.